Regulatory Barriers Hinder Access to Child Nutrition Programs

September 20, 2023

Article written by Michael Lyle and published by the Nevada Current

On a recent 103-degree August day, Three Square Food Bank CEO Beth Martino visited an apartment complex where the nonprofit delivers free meals to children during the summer.

The federally funded Summer Food Service Program provides free meals to children during a time they often lack access to free lunches they would normally receive in the school year.

But some of the federal requirements attached to the program, including requiring kids to physically eat next to the van distributing the meals rather than take food inside their homes where it’s cool, can be quite burdensome, Martino said.

“While I was glad to see everyone getting fed, there was a mom who sat down on a curb in a hot parking lot with her three children under the age of five so they could eat a sandwich,” she said.

Though she believes the regulation was well-intended to ensure children had access to food, it was among numerous examples Martino recently described to Democratic U.S. Rep. Susie Lee of how federal requirements attached to funding can sometimes create needless obstacles to feeding children.

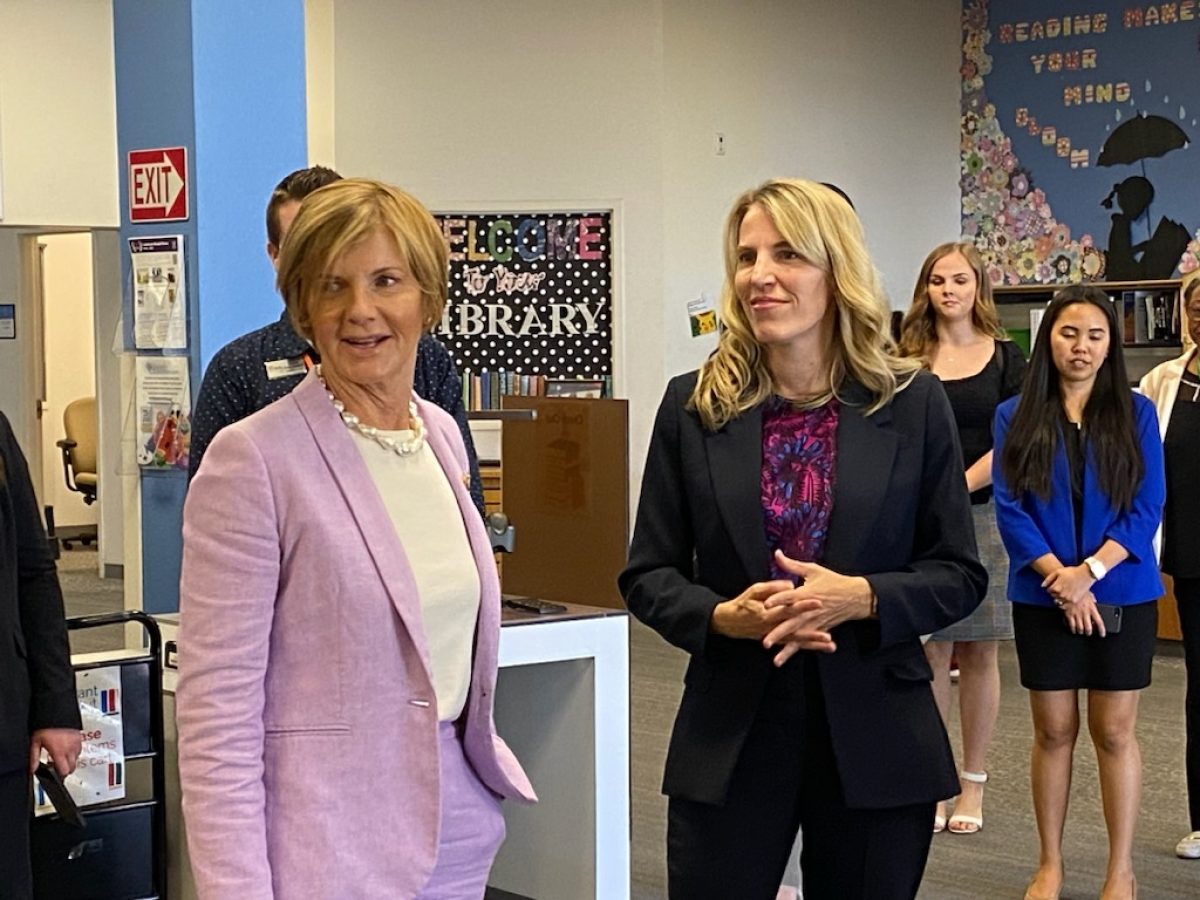

Lee met with Three Square Food Bank, representatives with the Las Vegas-Clark County Library District, and Head Start programs last week to discuss access to child nutrition.

The roundtable, Lee said, was to learn more about the programs and identify regulatory barriers that hinder groups from providing food to children. The event also comes ahead of Congress preparing to reauthorize spending in the latest Agriculture Improvement Act, commonly called the farm bill, this fall. Ongoing fights over that legislation threaten its passage, and in turn the capacity of nonprofits to distribute food.

The farm bill is set to expire Sept. 30. If it isn’t passed, along with government funding bills, there could be a partial government shutdown.

Burdensome federal regulations

An estimated 274,000 people, including 94,000 children, in Nevada face hunger each year.

Three Square Food Bank, which distributes food to pantries and runs meal programs for children and seniors, estimates one in six children live in a food-insecure household. Martino said people use a patchwork of options to address food insecurity that could include receiving SNAP benefits, visiting food pantries and attending a free congregate meal.

“If you take any one of those things away, suddenly there is a huge gap,” she said.

Three Square served 360,000 meals last year through its Child and Adult Care Food Program, which runs during the school year, and the Summer Food Service Program. Martino said there is a fair amount of work that needs to be done to administer those programs.

“We would like to do more than that because we know the need is greater,” she said.

However, the federal funding comes with regulations on how to administer those programs, many which are inconsistent and amount to needless hoops.

The Child and Adult Care Food Program requires them to collect the first and last name of all children, which isn’t required in the summer program. That requirement can be at odds with the library district, a distribution site, which has a patron privacy policy to not collect first and last names. Representatives with the library said they’ve been able to collect the first name and last initial as a workaround.

Martin said she understands concerns about fraud, but when it comes to children getting fed “the question I ask is do you really think a child is coming to the library to try to game the system? If they are there for a meal, it’s because they need a meal,” she said. “Let’s just feed children and not get wrapped around the paperwork.”

Though Clark County doesn’t have the same issues rural areas see, there are still parts of the Las Vegas area where children struggle to get to food distribution sites for free meals during the summer. Three Square operates a van to take meals to those areas, usually apartment complexes.

“I’m thrilled we are able to do that and get to apartment complexes where kids may not have transportation but they are there all day and might not get a meal,” she said.

Beating – or at least acknowledging – the heat

Federal regulations for the program require children to physically eat their meals while sitting next to the van. Martino said they started packing chairs to give children a place to sit, but sometimes those run out.

The biggest issue comes in the triple-digit heat. While the nonprofit can apply for a weather waiver that would allow children to take food with them, it is forced to re-apply every day it does distribution, and that first requires the National Weather Service to sign off.

“It’s heartbreaking to see kids having to stand in 100 degree heat to eat a sandwich while they stand by our truck because that’s what the regulation requires,” Martino said. “They can’t take that sandwich back to their apartment.” Lee said she would reach out to see if instead there could be a blanket heat waiver for when the “temperature is above 90 degrees, or whatever it is,” that would apply from May through September.

While there wasn’t a consensus where some of the regulations stemmed from, Martino said her best guess was policies were put in place to address concerns of potential fraud. Martino often receives questions from the community about what’s being done “to make sure people aren’t taking advantage of the charitable food network?”

“I find it hard to believe there is a massive effort to take advantage of a free meal being offered to children and at food pantries,” she said. “We just don’t see that.”

Another potential reason behind the regulation, she theorized, was to ensure children are actually consuming the meals rather than taking it home and giving it to another member of the household also dealing with hunger. “I think it came from a good place to make sure … we are getting a meal in the child’s hands and they are able to consume it,” she said. “But practically how we are carrying that out is challenging.”

As much as those at the roundtable hoped some of the barriers they face could be addressed, first they are waiting to see the status of the farm bill.

Martino said the organization is trying to figure out what a partial shutdown could mean for the food pantry, including how to meet the potential need that comes from furloughed government workers and SNAP recipients not receiving payments, and how to temporarily cover costs when they don’t receive federal reimbursements.

“In the last government shutdown because you were able to pass a continuing resolution right before we entered a shutdown, they proceeded to get benefit payments,” she said. “We are not sure if that would happen in this case. If you don’t pass a continuing resolution it is likely beneficiaries will go entirely without.”